A storm is brewing off the coast of South Carolina.

Anyone who has ever stood at the edge of the sea with a storm brewing knows the feeling: you see the sky darken and feel the temperature drop as the wind picks up. You feel that mixture of chills and excitement. As you watch the waves get more intense, the drizzle of rain turns to a downpour and you run for cover.

Pictured above: a view of an incoming rainstorm as seen from Oyster Landing, North Inlet, SC. (Source: Alex Barth)

Storms can take a physical toll on coastal environments in very visible ways, like flooding and beach erosion: but they also impact the organisms that live in the water. When beachgoers take cover during a storm, what’s happening at or below the surface?

Alex Barth has thought a lot about this.

Dr. Barth recently completed his PhD in the Stone Lab at the University of South Carolina where he investigated the impact of storms on organisms in estuaries, with a particular focus on phytoplankton analysis with FlowCam. He conducted his research in the North Inlet area of South Carolina—a part of the North Inlet-Winyah Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR).

Coastal areas like this face many risks as the frequency and intensity of storms increase. Risk assessments can help researchers, coastal managers, and municipalities characterize an area’s unique vulnerabilities.

Pictured here: map of the North Inlet-Winyah Bay Reserve in South Carolina. (Source)

According to Dr. Barth, “North Inlet was ranked as a highly vulnerable system…Yet, in the same risk assessment, the impact of major rainfall events on the North Inlet estuary was listed as a major uncertainty.” One specific area of uncertainty is the impact that storms may have on plankton communities.

Plankton are incredibly important because they form the base of all aquatic food webs. This is especially true in estuaries—highly productive areas that serve as nurseries for higher trophic level animals. Storms can impact a variety of variables, including salinity and nutrients.

Thanks to long-term time series data available through the NERR, Dr. Barth had access to chlorophyll-a data to see how phytoplankton biomass in the North Inlet has broadly fluctuated in response to storms. However, the total biomass in a system doesn’t necessarily tell the whole story: the types of plankton also matter because phytoplankton species present in an ecosystem can impact zooplankton.

Zooplankton are tiny predators that feed on phytoplankton and form an essential trophic connection to higher-order animals like fish. Many economically important organisms, like oysters, clams, crabs & lobsters, also start their life cycle as zooplankton.

Understanding the impact of storms on phytoplankton requires investigating many different variables, including salinity, nutrients, physical mixing, and more. Teasing apart all these variables in a reproducible way requires all of these inputs to be tested across a gradient, and for those tests to be replicated to quantify error.

That’s a lot of samples. A “storm in a bottle,” as Dr. Barth calls them.

Pictured here: “Storm in a bottle”; Dr. Barth and his experimental setup for testing the impact on rainwater additions to determine phytoplankton growth and community structure. (Source: Alex Barth)

Pictured here: “Storm in a bottle”; Dr. Barth and his experimental setup for testing the impact on rainwater additions to determine phytoplankton growth and community structure. (Source: Alex Barth)

If he had used manual microscopy to image, count, measure, and identify all of these factors, Dr. Barth would not have been able to accomplish the work in time to finish his thesis.

“[FlowCam] made the phytoplankton project I wanted to work on possible. It would not have been feasible if I had just used inverted microscopy because counting all those cells would have been such a time-consuming effort.”

The ability to automatically measure particles was key, too: while counting the number of cells (abundance) is important, it doesn’t tell us anything about the size of the organisms (biomass) and how they contribute to the composition of the community. This is where techniques like flow imaging microscopy with FlowCam extend what’s possible.

In Dr. Barth’s view, “Looking at things like biomass is much more valuable than thinking about just abundance, which…is what I've previously done using the Utermöhl method [on a microscope].”

Looking at changes in biovolume and community composition using FlowCam can also help researchers like Dr. Barth better interpret their observations. For example, he noticed from HPLC data that treatments where he added a higher proportion of runoff water corresponded to a huge boost in fucoxanthin, indicating the growth of diatoms. Using FlowCam to uncover which specific types of diatoms were responding—and combining this with tracking changes in diatom biovolume on a cell-by-cell basis—helped Dr. Barth discern whether different types of diatoms responded to different treatments.

Ultimately, he found that diatoms appear to capitalize on nutrient additions from runoff during storms. However, how they grow is species-specific, and unfiltered runoff may also introduce seed populations of cyanobacteria and other freshwater phytoplankton.

Pictured above: an excerpt from Dr. Barth’s PhD defense, showcasing a variety of diatoms he observed with FlowCam during his experiments such as Rhizosolenia (far right), Skeletonema, and Baccilaria. (Source: Alex Barth).

Pictured above: an excerpt from Dr. Barth’s PhD defense, showcasing a variety of diatoms he observed with FlowCam during his experiments such as Rhizosolenia (far right), Skeletonema, and Baccilaria. (Source: Alex Barth).

Just as with any scientific endeavor, the project was not without its challenges, especially considering the limited amount of time. Dr. Barth was the recipient of the 2023-24 FlowCam Aquatic Research Grant program for Graduate Students, which gave him access to a FlowCam 8100 instrument for one semester.

One challenge Dr. Barth overcame was determining the best procedure for filtering and diluting his samples to prevent clogging. He also wrote scripts to help deal with stuck particles and to reduce the number of clicks it took to get his data into an online database.

For someone like Dr. Barth who was originally trained on a microscope, “translating microscopy taxonomy knowledge to imagery taxonomy knowledge [was also] a bit of a bridge, but now there are people who have only ever worked with imaging tools, just because of how useful they are.”

Overall, the benefits of FlowCam far outpaced the challenges he encountered and overcame.

"The process of running it all through is very smooth and you can get a lot of data really, really quickly.” The speed at which FlowCam segments particles “is pretty unparalleled” compared to other imaging instruments, and FlowCam's “ease of operability is much higher from the software side."

So, what’s next for Alex Barth? He accelerated his thesis defense to start a postdoc at the University of Texas in Austin where he’s already putting some of his FlowCam experience to use. He hopes to publish two papers using the FlowCam data he collected during his thesis. “I was really impressed with FlowCam,” he reflected. “The quantity of data that you get with such a small sample—[and] the amount of information that you can extract—is just so useful.”

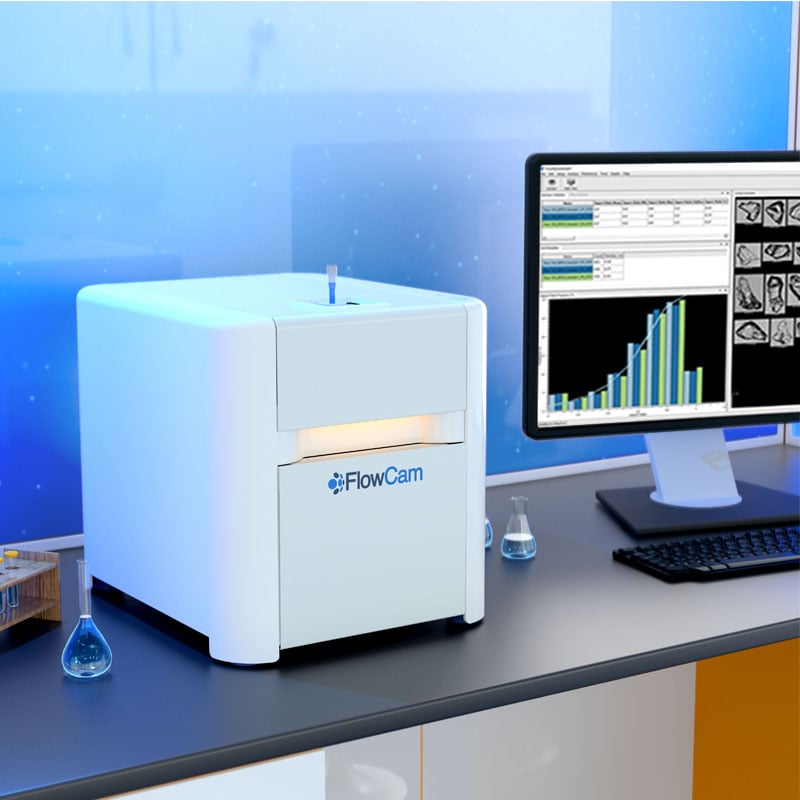

Pictured above: Dr. Alex Barth and his PhD advisor, Dr. Josh Stone, with FlowCam and some of their phytoplankton images.

Read about the large variety of research projects that FlowCam has contributed to in our Bibliography, and stay up to date on the latest FlowCam news and research by subscribing to our newsletter.